The Solar System[d] is the gravitationally bound system of the Sun and the objects that orbit it.[11] It formed about 4.6 billion years ago when a dense region of a molecular cloud collapsed, forming the Sun and a protoplanetary disc. The Sun is a typical star that maintains a balanced equilibrium by the fusion of hydrogen into helium at its core, releasing this energy from its outer photosphere. Astronomers classify it as a G-type main-sequence star.

The largest objects that orbit the Sun are the eight planets. In order from the Sun, they are four terrestrial planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars); two gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn); and two ice giants (Uranus and Neptune). All terrestrial planets have solid surfaces. Inversely, all giant planets do not have a definite surface, as they are mainly composed of gases and liquids. Over 99.86% of the Solar System’s mass is in the Sun and nearly 90% of the remaining mass is in Jupiter and Saturn.

There is a strong consensus among astronomers[e] that the Solar System has at least nine dwarf planets: Ceres, Orcus, Pluto, Haumea, Quaoar, Makemake, Gonggong, Eris, and Sedna. There are a vast number of small Solar System bodies, such as asteroids, comets, centaurs, meteoroids, and interplanetary dust clouds. Some of these bodies are in the asteroid belt (between Mars’s and Jupiter’s orbit) and the Kuiper belt (just outside Neptune’s orbit).[f] Six planets, seven dwarf planets, and other bodies have orbiting natural satellites, which are commonly called ‘moons’.

The Solar System is constantly flooded by the Sun’s charged particles, the solar wind, forming the heliosphere. Around 75–90 astronomical units from the Sun,[g] the solar wind is halted, resulting in the heliopause. This is the boundary of the Solar System to interstellar space. The outermost region of the Solar System is the theorized Oort cloud, the source for long-period comets, extending to a radius of 2,000–200,000 AU. The closest star to the Solar System, Proxima Centauri, is 4.25 light-years (269,000 AU) away. Both stars belong to the Milky Way galaxy.

Formation and evolution

Main article: Formation and evolution of the Solar System

Past

The Solar System formed at least 4.568 billion years ago from the gravitational collapse of a region within a large molecular cloud.[b] This initial cloud was likely several light-years across and probably birthed several stars.[14] As is typical of molecular clouds, this one consisted mostly of hydrogen, with some helium, and small amounts of heavier elements fused by previous generations of stars.[15]

As the pre-solar nebula[15] collapsed, conservation of angular momentum caused it to rotate faster. The center, where most of the mass collected, became increasingly hotter than the surroundings.[14] As the contracting nebula spun faster, it began to flatten into a protoplanetary disc with a diameter of roughly 200 AU[14][16] and a hot, dense protostar at the center.[17][18] The planets formed by accretion from this disc,[19] in which dust and gas gravitationally attracted each other, coalescing to form ever larger bodies. Hundreds of protoplanets may have existed in the early Solar System, but they either merged or were destroyed or ejected, leaving the planets, dwarf planets, and leftover minor bodies.[20][21]

Due to their higher boiling points, only metals and silicates could exist in solid form in the warm inner Solar System close to the Sun (within the frost line). They eventually formed the rocky planets of Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. Because these refractory materials only comprised a small fraction of the solar nebula, the terrestrial planets could not grow very large.[20]

The giant planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) formed further out, beyond the frost line, the point between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter where material is cool enough for volatile icy compounds to remain solid. The ices that formed these planets were more plentiful than the metals and silicates that formed the terrestrial inner planets, allowing them to grow massive enough to capture large atmospheres of hydrogen and helium, the lightest and most abundant elements.[20] Leftover debris that never became planets congregated in regions such as the asteroid belt, Kuiper belt, and Oort cloud.[20]

Within 50 million years, the pressure and density of hydrogen in the center of the protostar became great enough for it to begin thermonuclear fusion.[22] As helium accumulates at its core, the Sun is growing brighter;[23] early in its main-sequence life its brightness was 70% that of what it is today.[24] The temperature, reaction rate, pressure, and density increased until hydrostatic equilibrium was achieved: the thermal pressure counterbalancing the force of gravity. At this point, the Sun became a main-sequence star.[25] Solar wind from the Sun created the heliosphere and swept away the remaining gas and dust from the protoplanetary disc into interstellar space.[23]

Following the dissipation of the protoplanetary disk, the Nice model proposes that gravitational encounters between planetisimals and the gas giants caused each to migrate into different orbits. This led to dynamical instability of the entire system, which scattered the planetisimals and ultimately placed the gas giants in their current positions. During this period, the grand tack hypothesis suggests that a final inward migration of Jupiter dispersed much of the asteroid belt, leading to the Late Heavy Bombardment of the inner planets.[26][27]

Present and future

The Solar System remains in a relatively stable, slowly evolving state by following isolated, gravitationally bound orbits around the Sun.[28] Although the Solar System has been fairly stable for billions of years, it is technically chaotic, and may eventually be disrupted. There is a small chance that another star will pass through the Solar System in the next few billion years. Although this could destabilize the system and eventually lead millions of years later to expulsion of planets, collisions of planets, or planets hitting the Sun, it would most likely leave the Solar System much as it is today.[29]

The Sun’s main-sequence phase, from beginning to end, will last about 10 billion years for the Sun compared to around two billion years for all other subsequent phases of the Sun’s pre-remnant life combined.[30] The Solar System will remain roughly as it is known today until the hydrogen in the core of the Sun has been entirely converted to helium, which will occur roughly 5 billion years from now. This will mark the end of the Sun’s main-sequence life. At that time, the core of the Sun will contract with hydrogen fusion occurring along a shell surrounding the inert helium, and the energy output will be greater than at present. The outer layers of the Sun will expand to roughly 260 times its current diameter, and the Sun will become a red giant. Because of its increased surface area, the surface of the Sun will be cooler (2,600 K (4,220 °F) at its coolest) than it is on the main sequence.[30]

The expanding Sun is expected to vaporize Mercury as well as Venus, and render Earth and Mars uninhabitable (possibly destroying Earth as well).[31][32] Eventually, the core will be hot enough for helium fusion; the Sun will burn helium for a fraction of the time it burned hydrogen in the core. The Sun is not massive enough to commence the fusion of heavier elements, and nuclear reactions in the core will dwindle. Its outer layers will be ejected into space, leaving behind a dense white dwarf, half the original mass of the Sun but only the size of Earth.[30] The ejected outer layers may form a planetary nebula, returning some of the material that formed the Sun—but now enriched with heavier elements like carbon—to the interstellar medium.[33][34]

General characteristics

Astronomers sometimes divide the Solar System structure into separate regions. The inner Solar System includes Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, and the bodies in the asteroid belt. The outer Solar System includes Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and the bodies in the Kuiper belt.[35] Since the discovery of the Kuiper belt, the outermost parts of the Solar System are considered a distinct region consisting of the objects beyond Neptune.[36]

Composition

Further information: List of Solar System objects and List of interstellar and circumstellar molecules

The principal component of the Solar System is the Sun, a G-type main-sequence star that contains 99.86% of the system’s known mass and dominates it gravitationally.[37] The Sun’s four largest orbiting bodies, the giant planets, account for 99% of the remaining mass, with Jupiter and Saturn together comprising more than 90%. The remaining objects of the Solar System (including the four terrestrial planets, the dwarf planets, moons, asteroids, and comets) together comprise less than 0.002% of the Solar System’s total mass.[h]

The Sun is composed of roughly 98% hydrogen and helium,[41] as are Jupiter and Saturn.[42][43] A composition gradient exists in the Solar System, created by heat and light pressure from the early Sun; those objects closer to the Sun, which are more affected by heat and light pressure, are composed of elements with high melting points. Objects farther from the Sun are composed largely of materials with lower melting points.[44] The boundary in the Solar System beyond which those volatile substances could coalesce is known as the frost line, and it lies at roughly five times the Earth’s distance from the Sun.[5]

Orbits

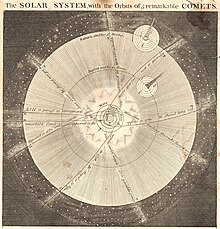

The planets and other large objects in orbit around the Sun lie near the plane of Earth’s orbit, known as the ecliptic. Smaller icy objects such as comets frequently orbit at significantly greater angles to this plane.[45][46] Most of the planets in the Solar System have secondary systems of their own, being orbited by natural satellites called moons. All of the largest natural satellites are in synchronous rotation, with one face permanently turned toward their parent. The four giant planets have planetary rings, thin discs of tiny particles that orbit them in unison.[47]

As a result of the formation of the Solar System, planets and most other objects orbit the Sun in the same direction that the Sun is rotating. That is, counter-clockwise, as viewed from above Earth’s north pole.[48] There are exceptions, such as Halley’s Comet.[49] Most of the larger moons orbit their planets in prograde direction, matching the direction of planetary rotation; Neptune’s moon Triton is the largest to orbit in the opposite, retrograde manner.[50] Most larger objects rotate around their own axes in the prograde direction relative to their orbit, though the rotation of Venus is retrograde.[51]

To a good first approximation, Kepler’s laws of planetary motion describe the orbits of objects around the Sun.[52]: 433–437 These laws stipulate that each object travels along an ellipse with the Sun at one focus, which causes the body’s distance from the Sun to vary over the course of its year. A body’s closest approach to the Sun is called its perihelion, whereas its most distant point from the Sun is called its aphelion.[53]: 9-6 With the exception of Mercury, the orbits of the planets are nearly circular, but many comets, asteroids, and Kuiper belt objects follow highly elliptical orbits. Kepler’s laws only account for the influence of the Sun’s gravity upon an orbiting body, not the gravitational pulls of different bodies upon each other. On a human time scale, these perturbations can be accounted for using numerical models,[53]: 9-6 but the planetary system can change chaotically over billions of years.[54]

The angular momentum of the Solar System is a measure of the total amount of orbital and rotational momentum possessed by all its moving components.[55] Although the Sun dominates the system by mass, it accounts for only about 2% of the angular momentum.[56][57] The planets, dominated by Jupiter, account for most of the rest of the angular momentum due to the combination of their mass, orbit, and distance from the Sun, with a possibly significant contribution from comets.[56]

Distances and scales

The radius of the Sun is 0.0047 AU (700,000 km; 400,000 mi).[58] Thus, the Sun occupies 0.00001% (1 part in 107) of the volume of a sphere with a radius the size of Earth’s orbit, whereas Earth’s volume is roughly 1 millionth (10−6) that of the Sun. Jupiter, the largest planet, is 5.2 AU from the Sun and has a radius of 71,000 km (0.00047 AU; 44,000 mi), whereas the most distant planet, Neptune, is 30 AU from the Sun.[43][59]

With a few exceptions, the farther a planet or belt is from the Sun, the larger the distance between its orbit and the orbit of the next nearest object to the Sun. For example, Venus is approximately 0.33 AU farther out from the Sun than Mercury, whereas Saturn is 4.3 AU out from Jupiter, and Neptune lies 10.5 AU out from Uranus. Attempts have been made to determine a relationship between these orbital distances, like the Titius–Bode law[60] and Johannes Kepler’s model based on the Platonic solids,[61] but ongoing discoveries have invalidated these hypotheses.[62]

Some Solar System models attempt to convey the relative scales involved in the Solar System in human terms. Some are small in scale (and may be mechanical—called orreries)—whereas others extend across cities or regional areas.[63] The largest such scale model, the Sweden Solar System, uses the 110-meter (361-foot) Avicii Arena in Stockholm as its substitute Sun, and, following the scale, Jupiter is a 7.5-meter (25-foot) sphere at Stockholm Arlanda Airport, 40 km (25 mi) away, whereas the farthest current object, Sedna, is a 10 cm (4 in) sphere in Luleå, 912 km (567 mi) away.[64][65] At that scale, the distance to Proxima Centauri would be roughly 8 times further than the Moon is from Earth.

If the Sun–Neptune distance is scaled to 100 metres (330 ft), then the Sun would be about 3 cm (1.2 in) in diameter (roughly two-thirds the diameter of a golf ball), the giant planets would be all smaller than about 3 mm (0.12 in), and Earth’s diameter along with that of the other terrestrial planets would be smaller than a flea (0.3 mm or 0.012 in) at this scale.[66]

Habitability

Main article: Planetary habitability in the Solar System

Comparison of the habitable zones of the Solar System and TRAPPIST-1, an ultracool red dwarf star known to have seven terrestrial planets in stable orbits around the star.

Comparison of the habitable zones for different stellar temperatures, with a sample of known exoplanets plus the Earth, Mars, and Venus. From top to bottom are an F-type main-sequence star, a yellow dwarf (G-type main-sequence star), an orange dwarf (K-type main-sequence star), a typical red dwarf, and an ultra-cool dwarf.

Besides solar energy, the primary characteristic of the Solar System enabling the presence of life is the heliosphere and planetary magnetic fields (for those planets that have them). These magnetic fields partially shield the Solar System from high-energy interstellar particles called cosmic rays. The density of cosmic rays in the interstellar medium and the strength of the Sun’s magnetic field change on very long timescales, so the level of cosmic-ray penetration in the Solar System varies, though by how much is unknown.[67]

The zone of habitability of the Solar System is conventionally located in the inner Solar System, where planetary surface or atmospheric temperatures admit the possibility of liquid water.[68] Habitability might be possible in subsurface oceans of various outer Solar System moons.[69]

Comparison with extrasolar systems

Compared to many extrasolar systems, the Solar System stands out in lacking planets interior to the orbit of Mercury.[70][71] The known Solar System lacks super-Earths, planets between one and ten times as massive as the Earth,[70] although the hypothetical Planet Nine, if it does exist, could be a super-Earth orbiting in the edge of the Solar System.[72]

Uncommonly, it has only small terrestrial and large gas giants; elsewhere planets of intermediate size are typical—both rocky and gas—so there is no “gap” as seen between the size of Earth and of Neptune (with a radius 3.8 times as large). As many of these super-Earths are closer to their respective stars than Mercury is to the Sun, a hypothesis has arisen that all planetary systems start with many close-in planets, and that typically a sequence of their collisions causes consolidation of mass into few larger planets, but in case of the Solar System the collisions caused their destruction and ejection.[70][73]

The orbits of Solar System planets are nearly circular. Compared to many other systems, they have smaller orbital eccentricity.[70] Although there are attempts to explain it partly with a bias in the radial-velocity detection method and partly with long interactions of a quite high number of planets, the exact causes remain undetermined.[70][74]

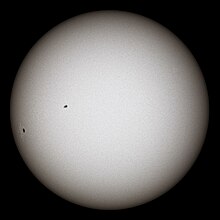

Sun

Main article: Sun

The Sun is the Solar System’s star and by far its most massive component. Its large mass (332,900 Earth masses),[75] which comprises 99.86% of all the mass in the Solar System,[76] produces temperatures and densities in its core high enough to sustain nuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium.[77] This releases an enormous amount of energy, mostly radiated into space as electromagnetic radiation peaking in visible light.[78][79]

Because the Sun fuses hydrogen at its core, it is a main-sequence star. More specifically, it is a G2-type main-sequence star, where the type designation refers to its effective temperature. Hotter main-sequence stars are more luminous but shorter lived. The Sun’s temperature is intermediate between that of the hottest stars and that of the coolest stars. Stars brighter and hotter than the Sun are rare, whereas substantially dimmer and cooler stars, known as red dwarfs, make up about 75% of the fusor stars in the Milky Way.[80]

The Sun is a population I star, having formed in the spiral arms of the Milky Way galaxy. It has a higher abundance of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium (“metals” in astronomical parlance) than the older population II stars in the galactic bulge and halo.[81] Elements heavier than hydrogen and helium were formed in the cores of ancient and exploding stars, so the first generation of stars had to die before the universe could be enriched with these atoms. The oldest stars contain few metals, whereas stars born later have more. This higher metallicity is thought to have been crucial to the Sun’s development of a planetary system because the planets formed from the accretion of “metals”.[82]

The region of space dominated by the Solar magnetosphere is the heliosphere, which spans much of the Solar System. Along with light, the Sun radiates a continuous stream of charged particles (a plasma) called the solar wind. This stream spreads outwards at speeds from 900,000 kilometres per hour (560,000 mph) to 2,880,000 kilometres per hour (1,790,000 mph),[83] filling the vacuum between the bodies of the Solar System. The result is a thin, dusty atmosphere, called the interplanetary medium, which extends to at least 100 AU.[84]

Activity on the Sun’s surface, such as solar flares and coronal mass ejections, disturbs the heliosphere, creating space weather and causing geomagnetic storms.[85] Coronal mass ejections and similar events blow a magnetic field and huge quantities of material from the surface of the Sun. The interaction of this magnetic field and material with Earth’s magnetic field funnels charged particles into Earth’s upper atmosphere, where its interactions create aurorae seen near the magnetic poles.[86] The largest stable structure within the heliosphere is the heliospheric current sheet, a spiral form created by the actions of the Sun’s rotating magnetic field on the interplanetary medium.[87][88]

Inner Solar System

The inner Solar System is the region comprising the terrestrial planets and the asteroids.[89] Composed mainly of silicates and metals,[90] the objects of the inner Solar System are relatively close to the Sun; the radius of this entire region is less than the distance between the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn. This region is within the frost line, which is a little less than 5 AU from the Sun.[45]

Inner planets

Main article: Terrestrial planet

The four terrestrial or inner planets have dense, rocky compositions, few or no moons, and no ring systems. They are composed largely of refractory minerals such as silicates—which form their crusts and mantles—and metals such as iron and nickel which form their cores. Three of the four inner planets (Venus, Earth, and Mars) have atmospheres substantial enough to generate weather; all have impact craters and tectonic surface features, such as rift valleys and volcanoes.[91]

- Mercury (0.31–0.59 AU from the Sun)[D 6] is the smallest planet in the Solar System. Its surface is grayish, with an expansive rupes (cliff) system generated from thrust faults and bright ray systems formed by impact event remnants.[92] The surface has widely varying temperature, with the equatorial regions ranging from −170 °C (−270 °F) at night to 420 °C (790 °F) during sunlight. In the past, Mercury was volcanically active, producing smooth basaltic plains similar to the Moon.[93] It is likely that Mercury has a silicate crust and a large iron core.[94][95] Mercury has a very tenuous atmosphere, consisting of solar-wind particles and ejected atoms.[96] Mercury has no natural satellites.[97]

- Venus (0.72–0.73 AU)[D 6] has a reflective, whitish atmosphere that is mainly composed of carbon dioxide. At the surface, the atmospheric pressure is ninety times as dense as on Earth’s sea level.[98] Venus has a surface temperatures over 400 °C (752 °F), mainly due to the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.[99] The planet lacks a protective magnetic field to protect against stripping by the solar wind, which suggests that its atmosphere is sustained by volcanic activity.[100] Its surface displays extensive evidence of volcanic activity with stagnant lid tectonics.[101] Venus has no natural satellites.[97]

- Earth (0.98–1.02 AU)[D 6] is the only place in the universe where life and surface liquid water are known to exist.[102] Earth’s atmosphere contains 78% nitrogen and 21% oxygen, which is the result of the presence of life.[103][104] The planet has a complex climate and weather system, with conditions differing drastically between climate regions.[105] The solid surface of Earth is dominated by green vegetation, deserts and white ice sheets.[106][107][108] Earth’s surface is shaped by plate tectonics that formed the continental masses.[93] Earth’s planetary magnetosphere shields the surface from radiation, limiting atmospheric stripping and maintaining life habitability.[109]

- The Moon is Earth’s only natural satellite.[110] Its diameter is one-quarter the size of Earth’s.[111] Its surface is covered in very fine regolith and dominated by impact craters.[112][113] Large dark patches on the Moon, maria, are formed from past volcanic activity.[114] The Moon’s atmosphere is extremely thin, consisting of a partial vacuum with particle densities of under 107 per cm−3.[115]

- Mars (1.38–1.67 AU)[D 6] has a radius about half of that of Earth.[116] Most of the planet is red due to iron oxide in Martian soil,[117] and the polar regions are covered in white ice caps made of water and carbon dioxide.[118] Mars has an atmosphere composed mostly of carbon dioxide, with surface pressure 0.6% of that of Earth, which is sufficient to support some weather phenomena.[119] During the Mars year (687 Earth days), there are large surface temperature swings on the surface between −78.5 °C (−109.3 °F) to 5.7 °C (42.3 °F). The surface is peppered with volcanoes and rift valleys, and has a rich collection of minerals.[120][121] Mars has a highly differentiated internal structure, and lost its magnetosphere 4 billion years ago.[122][123]Mars has two tiny moons:[124]

- Phobos is Mars’s inner moon. It is a small, irregularly shaped object with a mean radius of 11 km (7 mi). Its surface is very unreflective and dominated by impact craters.[D 7][125] In particular, Phobos’s surface has a very large Stickney impact crater that is roughly 4.5 km (2.8 mi) in radius.[126]

- Deimos is Mars’s outer moon. Like Phobos, it is irregularly shaped, with a mean radius of 6 km (4 mi) and its surface reflects little light.[D 8][D 9] However, the surface of Deimos is noticeably smoother than Phobos because the regolith partially covers the impact craters.[127]

Asteroids

Main article: Asteroid

Asteroids except for the largest, Ceres, are classified as small Solar System bodies and are composed mainly of carbonaceous, refractory rocky and metallic minerals, with some ice.[128][129] They range from a few meters to hundreds of kilometers in size. Many asteroids are divided into asteroid groups and families based on their orbital characteristics. Some asteroids have natural satellites that orbit them, that is, asteroids that orbit larger asteroids.[130]

- Mercury-crossing asteroids are those with perihelia within the orbit of Mercury. At least 362 are known to date, and include the closest objects to the Sun known in the Solar System.[131] No vulcanoids, asteroids between the orbit of Mercury and the Sun, have been discovered.[132][133] As of 2024, one asteroid has been discovered to orbit completely within Venus’s orbit, 594913 ꞌAylóꞌchaxnim.[134]

- Venus-crossing asteroids are those that cross the orbit of Venus. There are 2,809 as of 2015.[135]

- Near-Earth asteroids have orbits that approach relatively close to Earth’s orbit,[136] and some of them are potentially hazardous objects because they might collide with Earth in the future.[137][138] There are over 37.000 known as of 2024.[139] A number of solar-orbiting meteoroids were large enough to be tracked in space before striking Earth. It is now widely accepted that collisions in the past have had a significant role in shaping the geological and biological history of Earth.[140]

- Mars-crossing asteroids are those with perhihelia above 1.3 AU which cross the orbit of Mars.[141] As of 2024, NASA lists 26,182 confirmed Mars-crossing asteroids.[135]

Asteroid belt

The asteroid belt occupies a torus-shaped region between 2.3 and 3.3 AU from the Sun, which lies between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. It is thought to be remnants from the Solar System’s formation that failed to coalesce because of the gravitational interference of Jupiter.[142] The asteroid belt contains tens of thousands, possibly millions, of objects over one kilometer in diameter.[143] Despite this, the total mass of the asteroid belt is unlikely to be more than a thousandth of that of Earth.[40] The asteroid belt is very sparsely populated; spacecraft routinely pass through without incident.[144]

Below are the descriptions of the three largest bodies in the asteroid belt. They are all considered to be relatively intact protoplanets, a precursor stage before becoming a fully-formed planet (see List of exceptional asteroids):[145][146][147]

- Ceres (2.55–2.98 AU) is the only dwarf planet in the asteroid belt.[148] It is the largest object in the belt, with a diameter of 940 km (580 mi).[149] Its surface contains a mixture of carbon,[150] frozen water and hydrated minerals.[151] There are signs of past cryovolcanic activity, where volatile material such as water are erupted onto the surface, as seen in surface bright spots.[152] Ceres has a very thin water vapor atmosphere, but practically speaking it is indistinguishable from a vacuum.[153]

- Vesta (2.13–3.41 AU) is the second-largest object in the asteroid belt.[154] Its fragments survive as the Vesta asteroid family[155] and numerous HED meteorites found on Earth.[156] Vesta’s surface, dominated by basaltic and metamorphic material, has a denser composition than Ceres’s.[157] Its surface is marked by two giant craters: Rheasilvia and Veneneia.[158]

- Pallas (2.15–2.57 AU) is the third-largest object in the asteroid belt.[154] It has its own Pallas asteroid family.[155] Not much is known about Pallas because it has never been visited by a spacecraft,[159] though its surface is predicted to be composed of silicates.[160]

Hilda asteroids are in a 3:2 resonance with Jupiter; that is, they go around the Sun three times for every two Jovian orbits.[161] They lie in three linked clusters between Jupiter and the main asteroid belt.

Trojans are bodies located within another body’s gravitationally stable Lagrange points: L4, 60° ahead in its orbit, or L5, 60° behind in its orbit.[162] Every planet except Mercury and Saturn is known to possess at least 1 trojan.[163][164][165] The Jupiter trojan population is roughly equal to that of the asteroid belt.[166] After Jupiter, Neptune possesses the most confirmed trojans, at 28.[167]

Outer Solar System

The outer region of the Solar System is home to the giant planets and their large moons. The centaurs and many short-period comets orbit in this region. Due to their greater distance from the Sun, the solid objects in the outer Solar System contain a higher proportion of volatiles such as water, ammonia, and methane, than planets of the inner Solar System because their lower temperatures allow these compounds to remain solid, without significant sublimation.[20]

Outer planets

Main article: Giant planet

The four outer planets, called giant planets or Jovian planets, collectively make up 99% of the mass orbiting the Sun.[h] All four giant planets have multiple moons and a ring system, although only Saturn’s rings are easily observed from Earth.[91] Jupiter and Saturn are composed mainly of gases with extremely low melting points, such as hydrogen, helium, and neon,[168] hence their designation as gas giants.[169] Uranus and Neptune are ice giants,[170] meaning they are largely composed of ‘ice’ in the astronomical sense (chemical compounds with melting points of up to a few hundred kelvins[168] such as water, methane, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and carbon dioxide.[171]) Icy substances comprise the majority of the satellites of the giant planets and small objects that lie beyond Neptune’s orbit.[171][172]

- Jupiter (4.95–5.46 AU)[D 6] is the biggest and most massive planet in the Solar System. On its surface, there are orange-brown and white cloud bands moving via the principles of atmospheric circulation, with giant storms swirling on the surface such as the Great Red Spot and white ‘ovals’. Jupiter possesses a strong enough magnetosphere to redirect ionizing radiation and cause auroras on its poles.[173] As of 2024, Jupiter has 95 confirmed satellites, which can roughly be sorted into three groups:

- The Amalthea group, consisting of Metis, Adrastea, Amalthea, and Thebe. They orbit substantially closer to Jupiter than other satellites.[174] Materials from these natural satellites are the source of Jupiter’s faint ring.[175]

- The Galilean moons, consisting of Ganymede, Callisto, Io, and Europa. They are the largest moons of Jupiter and exhibit planetary properties.[176]

- Irregular satellites, consisting of substantially smaller natural satellites. They have more distant orbits than the other objects.[177]

- Saturn (9.08–10.12 AU)[D 6] has a distinctive visible ring system orbiting around its equator composed of small ice and rock particles. Like Jupiter, it is mostly made of hydrogen and helium.[178] At its north and south poles, Saturn has peculiar hexagon-shaped storms larger than the diameter of Earth. Saturn has a magnetosphere capable of producing weak auroras. As of 2024, Saturn has 146 confirmed satellites, grouped into:

- Ring moonlets and shepherds, which orbit inside or close to Saturn’s rings. A moonlet can only partially clear out dust in its orbit,[179] while the ring shepherds are able to completely clear out dust, forming visible gaps in the rings.[180]

- Inner large satellites Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, and Dione. These satellites orbit within Saturn’s E ring. They are composed mostly of water ice and are believed to have differentiated internal structures.[181]

- Trojan moons Calypso and Telesto (trojans of Tethys), and Helene and Polydeuces (trojans of Dione). These small moons share their orbits with Tethys and Dione, leading or trailing either.[182][183]

- Outer large satellites Rhea, Titan, Hyperion, and Iapetus.[181] Titan is the only satellite in the Solar System to have a substantial atmosphere.[184]

- Irregular satellites, consisting of substantially smaller natural satellites. They have more distant orbits than the other objects. Phoebe is the largest irregular satellite of Saturn.[185]

- Uranus (18.3–20.1 AU),[D 6] uniquely among the planets, orbits the Sun on its side with an axial tilt >90°. This gives the planet extreme seasonal variation as each pole points alternately toward and then away from the Sun.[186] Uranus’ outer layer has a muted cyan color, but underneath these clouds are many mysteries about its climate, such as unusually low internal heat and erratic cloud formation. As of 2024, Uranus has 28 confirmed satellites, divided into three groups:

- Inner satellites, which orbit inside Uranus’ ring system.[187] They are very close to each other, which suggests that their orbits are chaotic.[188]

- Large satellites, consisting of Titania, Oberon, Umbriel, Ariel, and Miranda.[189] Most of them have roughly equal amounts of rock and ice, except Miranda, which is made primarily of ice.[190]

- Irregular satellites, having more distant and eccentric orbits than the other objects.[191]

- Neptune (29.9–30.5 AU)[D 6] is the furthest planet known in the Solar System. Its outer atmosphere has a slightly muted cyan color, with occasional storms on the surface that look like dark spots. Like Uranus, many atmospheric phenomena of Neptune are unexplained, such as the thermosphere‘s abnormally high temperature or the strong tilt (47°) of its magnetosphere. As of 2024, Neptune has 16 confirmed satellites, divided into two groups:

- Regular satellites, which have circular orbits that lie near Neptune’s equator.[185]

- Irregular satellites, which as the name implies, have less regular orbits. One of them, Triton, is Neptune’s largest moon. It is geologically active, with erupting geysers of nitrogen gas, and possesses a thin, cloudy nitrogen atmosphere.[192][184]

Centaurs

Main article: Centaur

The centaurs are icy, comet-like bodies whose semi-major axes are longer than Jupiter’s and shorter than Neptune’s (between 5.5 and 30 AU). These are former Kuiper belt and scattered disc objects (SDOs) that were gravitationally perturbed closer to the Sun by the outer planets, and are expected to become comets or be ejected out of the Solar System.[39] While most centaurs are inactive and asteroid-like, some exhibit cometary activity, such as the first centaur discovered, 2060 Chiron, which has been classified as a comet (95P) because it develops a coma just as comets do when they approach the Sun.[193] The largest known centaur, 10199 Chariklo, has a diameter of about 250 km (160 mi) and is one of the few minor planets possessing a ring system.[194][195]

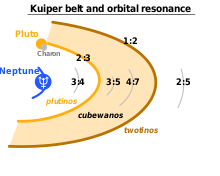

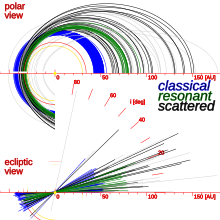

Trans-Neptunian region

Beyond the orbit of Neptune lies the area of the “trans-Neptunian region“, with the doughnut-shaped Kuiper belt, home of Pluto and several other dwarf planets, and an overlapping disc of scattered objects, which is tilted toward the plane of the Solar System and reaches much further out than the Kuiper belt. The entire region is still largely unexplored. It appears to consist overwhelmingly of many thousands of small worlds—the largest having a diameter only a fifth that of Earth and a mass far smaller than that of the Moon—composed mainly of rock and ice. This region is sometimes described as the “third zone of the Solar System”, enclosing the inner and the outer Solar System.[196]

Kuiper belt

Main article: Kuiper belt

The Kuiper belt is a great ring of debris similar to the asteroid belt, but consisting mainly of objects composed primarily of ice.[197] It extends between 30 and 50 AU from the Sun. It is composed mainly of small Solar System bodies, although the largest few are probably large enough to be dwarf planets.[198] There are estimated to be over 100,000 Kuiper belt objects with a diameter greater than 50 km (30 mi), but the total mass of the Kuiper belt is thought to be only a tenth or even a hundredth the mass of Earth.[39] Many Kuiper belt objects have satellites,[199] and most have orbits that are substantially inclined (~10°) to the plane of the ecliptic.[200]

The Kuiper belt can be roughly divided into the “classical” belt and the resonant trans-Neptunian objects.[197] The latter have orbits whose periods are in a simple ratio to that of Neptune: for example, going around the Sun twice for every three times that Neptune does, or once for every two. The classical belt consists of objects having no resonance with Neptune, and extends from roughly 39.4 to 47.7 AU.[201] Members of the classical Kuiper belt are sometimes called “cubewanos”, after the first of their kind to be discovered, originally designated 1992 QB1, (and has since been named Albion); they are still in near primordial, low-eccentricity orbits.[202]

There is strong consensus among astronomers that five members of the Kuiper belt are dwarf planets.[198][203] Many dwarf planet candidates are being considered, pending further data for verification.[204]

- Pluto (29.7–49.3 AU) is the largest known object in the Kuiper belt. Pluto has a relatively eccentric orbit, inclined 17 degrees to the ecliptic plane. Pluto has a 2:3 resonance with Neptune, meaning that Pluto orbits twice around the Sun for every three Neptunian orbits. Kuiper belt objects whose orbits share this resonance are called plutinos.[205]Pluto has five moons: Charon, Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra.[206]

- Charon, the largest of Pluto’s moons, is sometimes described as part of a binary system with Pluto, as the two bodies orbit a barycenter of gravity above their surfaces (i.e. they appear to “orbit each other”).

- Orcus (30.3–48.1 AU), is in the same 2:3 orbital resonance with Neptune as Pluto, and is the largest such object after Pluto itself.[207] Its eccentricity and inclination are similar to Pluto’s, but its perihelion lies about 120° from that of Pluto. Thus, the phase of Orcus’s orbit is opposite to Pluto’s: Orcus is at aphelion (most recently in 2019) around when Pluto is at perihelion (most recently in 1989) and vice versa.[208] For this reason, it has been called the anti-Pluto.[209][210] It has one known moon, Vanth.[211]

- Haumea (34.6–51.6 AU) was discovered in 2005.[212] It is in a temporary 7:12 orbital resonance with Neptune.[207] Haumea possesses a ring system, two known moons named Hiʻiaka and Namaka, and rotates so quickly (once every 3.9 hours) that it is stretched into an ellipsoid. It is part of a collisional family of Kuiper belt objects that share similar orbits, which suggests a giant impact on Haumea ejected fragments into space billions of years ago.[213]

- Makemake (38.1–52.8 AU), although smaller than Pluto, is the largest known object in the classical Kuiper belt (that is, a Kuiper belt object not in a confirmed resonance with Neptune). Makemake is the brightest object in the Kuiper belt after Pluto. Discovered in 2005, it was officially named in 2009.[214] Its orbit is far more inclined than Pluto’s, at 29°.[215] It has one known moon, S/2015 (136472) 1.[216]

- Quaoar (41.9–45.5 AU) is the second-largest known object in the classical Kuiper belt, after Makemake. Its orbit is significantly less eccentric and inclined than those of Makemake or Haumea.[207] It possesses a ring system and one known moon, Weywot.[217]

Scattered disc

Main article: Scattered disc

The scattered disc, which overlaps the Kuiper belt but extends out to near 500 AU, is thought to be the source of short-period comets. Scattered-disc objects are believed to have been perturbed into erratic orbits by the gravitational influence of Neptune’s early outward migration. Most scattered disc objects have perihelia within the Kuiper belt but aphelia far beyond it (some more than 150 AU from the Sun). SDOs’ orbits can be inclined up to 46.8° from the ecliptic plane.[218] Some astronomers consider the scattered disc to be merely another region of the Kuiper belt and describe scattered-disc objects as “scattered Kuiper belt objects”.[219] Some astronomers classify centaurs as inward-scattered Kuiper belt objects along with the outward-scattered residents of the scattered disc.[220]

Currently, there is strong consensus among astronomers that two of the bodies in the scattered disc are dwarf planets:

- Eris (38.3–97.5 AU) is the largest known scattered disc object and the most massive known dwarf planet. Eris’s discovery contributed to a debate about the definition of a planet because it is 25% more massive than Pluto[221] and about the same diameter. It has one known moon, Dysnomia. Like Pluto, its orbit is highly eccentric, with a perihelion of 38.2 AU (roughly Pluto’s distance from the Sun) and an aphelion of 97.6 AU, and steeply inclined to the ecliptic plane at an angle of 44°.[222]

- Gonggong (33.8–101.2 AU) is a dwarf planet in a comparable orbit to Eris, except that it is in a 3:10 resonance with Neptune.[D 10] It has one known moon, Xiangliu.[223]

Extreme trans-Neptunian objects

Main article: Extreme trans-Neptunian object

Some objects in the Solar System have a very large orbit, and therefore are much less affected by the known giant planets than other minor planet populations. These bodies are called extreme trans-Neptunian objects, or ETNOs for short.[224] Generally, ETNOs’ semi-major axes are at least 150–250 AU wide.[224][225] For example, 541132 Leleākūhonua orbits the Sun once every ~32,000 years, with a distance of 65–2000 AU from the Sun.[D 11]

This population is divided into three subgroups by astronomers. The scattered ETNOs have perihelia around 38–45 AU and an exceptionally high eccentricity of more than 0.85. As with the regular scattered disc objects, they were likely formed as result of gravitational scattering by Neptune and still interact with the giant planets. The detached ETNOs, with perihelia approximately between 40–45 and 50–60 AU, are less affected by Neptune than the scattered ETNOs, but are still relatively close to Neptune. The sednoids or inner Oort cloud objects, with perihelia beyond 50–60 AU, are too far from Neptune to be strongly influenced by it.[224]

Currently, there is one ETNO that is classified as a dwarf planet:

- Sedna (76.2–937 AU) was the first extreme trans-Neptunian object to be discovered. It is a large, reddish object, and it takes ~11,400 years for Sedna to complete one orbit. Mike Brown, who discovered the object in 2003, asserts that it cannot be part of the scattered disc or the Kuiper belt because its perihelion is too distant to have been affected by Neptune’s migration.[226] The sednoid population is named after Sedna.[224]

Edge of the heliosphere

The Sun’s stellar-wind bubble, the heliosphere, a region of space dominated by the Sun, has its boundary at the termination shock. Based on the Sun’s peculiar motion relative to the local standard of rest, this boundary is roughly 80–100 AU from the Sun upwind of the interstellar medium and roughly 200 AU from the Sun downwind.[227] Here the solar wind collides with the interstellar medium[228] and dramatically slows, condenses and becomes more turbulent, forming a great oval structure known as the heliosheath.[227]

The heliosheath has been theorized to look and behave very much like a comet’s tail, extending outward for a further 40 AU on the upwind side but tailing many times that distance downwind to possibly several thousands of AU.[229][230] Evidence from the Cassini and Interstellar Boundary Explorer spacecraft has suggested that it is forced into a bubble shape by the constraining action of the interstellar magnetic field,[231][232] but the actual shape remains unknown.[233]

The shape and form of the outer edge of the heliosphere is likely affected by the fluid dynamics of interactions with the interstellar medium as well as solar magnetic fields prevailing to the south, e.g. it is bluntly shaped with the northern hemisphere extending 9 AU farther than the southern hemisphere.[227] The heliopause is considered the beginning of the interstellar medium.[84] Beyond the heliopause, at around 230 AU, lies the bow shock: a plasma “wake” left by the Sun as it travels through the Milky Way.[234] Large objects outside the heliopause remain gravitationally bound to the Sun, but the flow of matter in the interstellar medium homogenizes the distribution of micro-scale objects.[84]

Miscellaneous populations

Comets

Main article: Comet

Comets are small Solar System bodies, typically only a few kilometers across, composed largely of volatile ices. They have highly eccentric orbits, generally a perihelion within the orbits of the inner planets and an aphelion far beyond Pluto. When a comet enters the inner Solar System, its proximity to the Sun causes its icy surface to sublimate and ionise, creating a coma: a long tail of gas and dust often visible to the naked eye.[235]

Short-period comets have orbits lasting less than two hundred years. Long-period comets have orbits lasting thousands of years. Short-period comets are thought to originate in the Kuiper belt, whereas long-period comets, such as Hale–Bopp, are thought to originate in the Oort cloud. Many comet groups, such as the Kreutz sungrazers, formed from the breakup of a single parent.[236] Some comets with hyperbolic orbits may originate outside the Solar System, but determining their precise orbits is difficult.[237] Old comets whose volatiles have mostly been driven out by solar warming are often categorized as asteroids.[238]

Meteoroids, meteors and dust

Main articles: Meteoroid, Interplanetary dust cloud, and Cosmic dust

Solid objects smaller than one meter are usually called meteoroids and micrometeoroids (grain-sized), with the exact division between the two categories being debated over the years.[239] By 2017, the IAU designated any solid object having a diameter between ~30 micrometers and 1 meter as meteoroids, and depreciated the micrometeoroid categorization, instead terms smaller particles simply as ‘dust particles’.[240]

Some meteoroids formed via disintegration of comets and asteroids, while a few formed via impact debris ejected from planetary bodies. Most meteoroids are made of silicates and heavier metals like nickel and iron.[241] When passing through the Solar System, comets produce a trail of meteoroids; it is hypothesized that this is caused either by vaporization of the comet’s material or by simple breakup of dormant comets. When crossing an atmosphere, these meteoroids will produce bright streaks in the sky due to atmospheric entry, called meteors. If a stream of meteoroids enter the atmosphere on parallel trajectories, the meteors will seemingly ‘radiate’ from a point in the sky, hence the phenomenon’s name: meteor shower.[242]

The inner Solar System is home to the zodiacal dust cloud, which is visible as the hazy zodiacal light in dark, unpolluted skies. It may be generated by collisions within the asteroid belt brought on by gravitational interactions with the planets; a more recent proposed origin is materials from planet Mars.[243] The outer Solar System hosts a cosmic dust cloud. It extends from about 10 AU to about 40 AU, and was probably created by collisions within the Kuiper belt.[244][245]

Boundary region and uncertainties

See also: Planets beyond Neptune, Planet Nine, and List of Solar System objects by greatest aphelion

Much of the Solar System is still unknown. Regions beyond thousands of AU away are still virtually unmapped and learning about this region of space is difficult. Study in this region depends upon inferences from those few objects whose orbits happen to be perturbed such that they fall closer to the Sun, and even then, detecting these objects has often been possible only when they happened to become bright enough to register as comets.[246] Many objects may yet be discovered in the Solar System’s uncharted regions.[247]

The Oort cloud is a theorized spherical shell of up to a trillion icy objects that is thought to be the source for all long-period comets.[248][249] No direct observation of the Oort cloud is possible with present imaging technology.[250] It is theorized to surround the Solar System at roughly 50,000 AU (~0.9 ly) from the Sun and possibly to as far as 100,000 AU (~1.8 ly). The Oort cloud is thought to be composed of comets that were ejected from the inner Solar System by gravitational interactions with the outer planets. Oort cloud objects move very slowly, and can be perturbed by infrequent events, such as collisions, the gravitational effects of a passing star, or the galactic tide, the tidal force exerted by the Milky Way.[248][249]

As of the 2020s, a few astronomers have hypothesized that Planet Nine (a planet beyond Neptune) might exist, based on statistical variance in the orbit of extreme trans-Neptunian objects.[251] Their closest approaches to the Sun are mostly clustered around one sector and their orbits are similarly tilted, suggesting that a large planet might be influencing their orbit over millions of years.[252][253][254] However, some astronomers said that this observation might be credited to observational biases or just sheer coincidence.[255] An alternative hypothesis has a close flyby of another star disrupting the outer Solar System.[256]

The Sun’s gravitational field is estimated to dominate the gravitational forces of surrounding stars out to about two light-years (125,000 AU). Lower estimates for the radius of the Oort cloud, by contrast, do not place it farther than 50,000 AU.[257] Most of the mass is orbiting in the region between 3,000 and 100,000 AU.[258] The furthest known objects, such as Comet West, have aphelia around 70,000 AU from the Sun.[259] The Sun’s Hill sphere with respect to the galactic nucleus, the effective range of its gravitational influence, is thought to extend up to a thousand times farther and encompasses the hypothetical Oort cloud.[260] It was calculated by G. A. Chebotarev to be 230,000 AU.[7]

Celestial neighborhood

Main articles: List of nearest stars, List of nearest exoplanets, and List of nearby stellar associations and moving groups

Within 10 light-years of the Sun there are relatively few stars, the closest being the triple star system Alpha Centauri, which is about 4.4 light-years away and may be in the Local Bubble’s G-Cloud.[262] Alpha Centauri A and B are a closely tied pair of Sun-like stars, whereas the closest star to the Sun, the small red dwarf Proxima Centauri, orbits the pair at a distance of 0.2 light-years. In 2016, a potentially habitable exoplanet was found to be orbiting Proxima Centauri, called Proxima Centauri b, the closest confirmed exoplanet to the Sun.[263]

The Solar System is surrounded by the Local Interstellar Cloud, although it is not clear if it is embedded in the Local Interstellar Cloud or if it lies just outside the cloud’s edge.[264] Multiple other interstellar clouds exist in the region within 300 light-years of the Sun, known as the Local Bubble.[264] The latter feature is an hourglass-shaped cavity or superbubble in the interstellar medium roughly 300 light-years across. The bubble is suffused with high-temperature plasma, suggesting that it may be the product of several recent supernovae.[265]

The Local Bubble is a small superbubble compared to the neighboring wider Radcliffe Wave and Split linear structures (formerly Gould Belt), each of which are some thousands of light-years in length.[266] All these structures are part of the Orion Arm, which contains most of the stars in the Milky Way that are visible to the unaided eye.[267]

Groups of stars form together in star clusters, before dissolving into co-moving associations. A prominent grouping that is visible to the naked eye is the Ursa Major moving group, which is around 80 light-years away within the Local Bubble. The nearest star cluster is Hyades, which lies at the edge of the Local Bubble. The closest star-forming regions are the Corona Australis Molecular Cloud, the Rho Ophiuchi cloud complex and the Taurus molecular cloud; the latter lies just beyond the Local Bubble and is part of the Radcliffe wave.[268]

Stellar flybys that pass within 0.8 light-years of the Sun occur roughly once every 100,000 years. The closest well-measured approach was Scholz’s Star, which approached to ~50,000 AU of the Sun some ~70 thousands years ago, likely passing through the outer Oort cloud.[269] There is a 1% chance every billion years that a star will pass within 100 AU of the Sun, potentially disrupting the Solar System.[270]

Galactic position

See also: Location of Earth, Galactic year, and Orbit of the Sun

The Solar System is located in the Milky Way, a barred spiral galaxy with a diameter of about 100,000 light-years containing more than 100 billion stars.[271] The Sun is part of one of the Milky Way’s outer spiral arms, known as the Orion–Cygnus Arm or Local Spur.[272][273] It is a member of the thin disk population of stars orbiting close to the galactic plane.[274]

Its speed around the center of the Milky Way is about 220 km/s, so that it completes one revolution every 240 million years.[271] This revolution is known as the Solar System’s galactic year.[275] The solar apex, the direction of the Sun’s path through interstellar space, is near the constellation Hercules in the direction of the current location of the bright star Vega.[276] The plane of the ecliptic lies at an angle of about 60° to the galactic plane.[c]

The Sun follows a nearly circular orbit around the Galactic Center (where the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* resides) at a distance of 26,660 light-years,[278] orbiting at roughly the same speed as that of the spiral arms.[279] If it orbited close to the center, gravitational tugs from nearby stars could perturb bodies in the Oort cloud and send many comets into the inner Solar System, producing collisions with potentially catastrophic implications for life on Earth. In this scenario, the intense radiation of the Galactic Center could interfere with the development of complex life.[279]

The Solar System’s location in the Milky Way is a factor in the evolutionary history of life on Earth. Spiral arms are home to a far larger concentration of supernovae, gravitational instabilities, and radiation that could disrupt the Solar System, but since Earth stays in the Local Spur and therefore does not pass frequently through spiral arms, this has given Earth long periods of stability for life to evolve.[279] However, according to the controversial Shiva hypothesis, the changing position of the Solar System relative to other parts of the Milky Way could explain periodic extinction events on Earth.[280][281]

Discovery and exploration

Main article: Discovery and exploration of the Solar System

Humanity’s knowledge of the Solar System has grown incrementally over the centuries. Up to the Late Middle Ages–Renaissance, astronomers from Europe to India believed Earth to be stationary at the center of the universe[282] and categorically different from the divine or ethereal objects that moved through the sky. Although the Greek philosopher Aristarchus of Samos had speculated on a heliocentric reordering of the cosmos, Nicolaus Copernicus was the first person known to have developed a mathematically predictive heliocentric system.[283][284]

Heliocentrism did not triumph immediately over geocentrism, but the work of Copernicus had its champions, notably Johannes Kepler. Using a heliocentric model that improved upon Copernicus by allowing orbits to be elliptical, and the precise observational data of Tycho Brahe, Kepler produced the Rudolphine Tables, which enabled accurate computations of the positions of the then-known planets. Pierre Gassendi used them to predict a transit of Mercury in 1631, and Jeremiah Horrocks did the same for a transit of Venus in 1639. This provided a strong vindication of heliocentrism and Kepler’s elliptical orbits.[285][286]

In the 17th century, Galileo publicized the use of the telescope in astronomy; he and Simon Marius independently discovered that Jupiter had four satellites in orbit around it.[287] Christiaan Huygens followed on from these observations by discovering Saturn’s moon Titan and the shape of the rings of Saturn.[288] In 1677, Edmond Halley observed a transit of Mercury across the Sun, leading him to realize that observations of the solar parallax of a planet (more ideally using the transit of Venus) could be used to trigonometrically determine the distances between Earth, Venus, and the Sun.[289] Halley’s friend Isaac Newton, in his magisterial Principia Mathematica of 1687, demonstrated that celestial bodies are not quintessentially different from Earthly ones: the same laws of motion and of gravity apply on Earth and in the skies.[52]: 142

The term “Solar System” entered the English language by 1704, when John Locke used it to refer to the Sun, planets, and comets.[290] In 1705, Halley realized that repeated sightings of a comet were of the same object, returning regularly once every 75–76 years. This was the first evidence that anything other than the planets repeatedly orbited the Sun,[291] though Seneca had theorized this about comets in the 1st century.[292] Careful observations of the 1769 transit of Venus allowed astronomers to calculate the average Earth–Sun distance as 93,726,900 miles (150,838,800 km), only 0.8% greater than the modern value.[293]

Uranus, having occasionally been observed since 1690 and possibly from antiquity, was recognized to be a planet orbiting beyond Saturn by 1783.[294] In 1838, Friedrich Bessel successfully measured a stellar parallax, an apparent shift in the position of a star created by Earth’s motion around the Sun, providing the first direct, experimental proof of heliocentrism.[295] Neptune was identified as a planet some years later, in 1846, thanks to its gravitational pull causing a slight but detectable variation in the orbit of Uranus.[296] Mercury’s orbital anomaly observations led to searches for Vulcan, a planet interior of Mercury, but these attempts were quashed with Albert Einstein‘s theory of general relativity in 1915.[297]

In the 20th century, humans began their space exploration around the Solar System, starting with placing telescopes in space since the 1960s.[298] By 1989, all eight planets have been visited by space probes.[299] Probes have returned samples from comets[300] and asteroids,[301] as well as flown through the Sun’s corona[302] and visited two dwarf planets (Pluto and Ceres).[303][304] To save on fuel, some space missions make use of gravity assist maneuvers, such as the two Voyager probes accelerating when flying by planets in the outer Solar System[305] and the Parker Solar Probe decelerating closer towards the Sun after its flyby of Venus.[306]

Humans have landed on the Moon during the Apollo program in the 1960s and 1970s[307] and will return to the Moon in the 2020s with the Artemis program.[308] Discoveries in the 20th and 21st century has prompted the redefinition of the term planet in 2006, hence the demotion of Pluto to a dwarf planet,[309] and further interest in trans-Neptunian objects.[310]